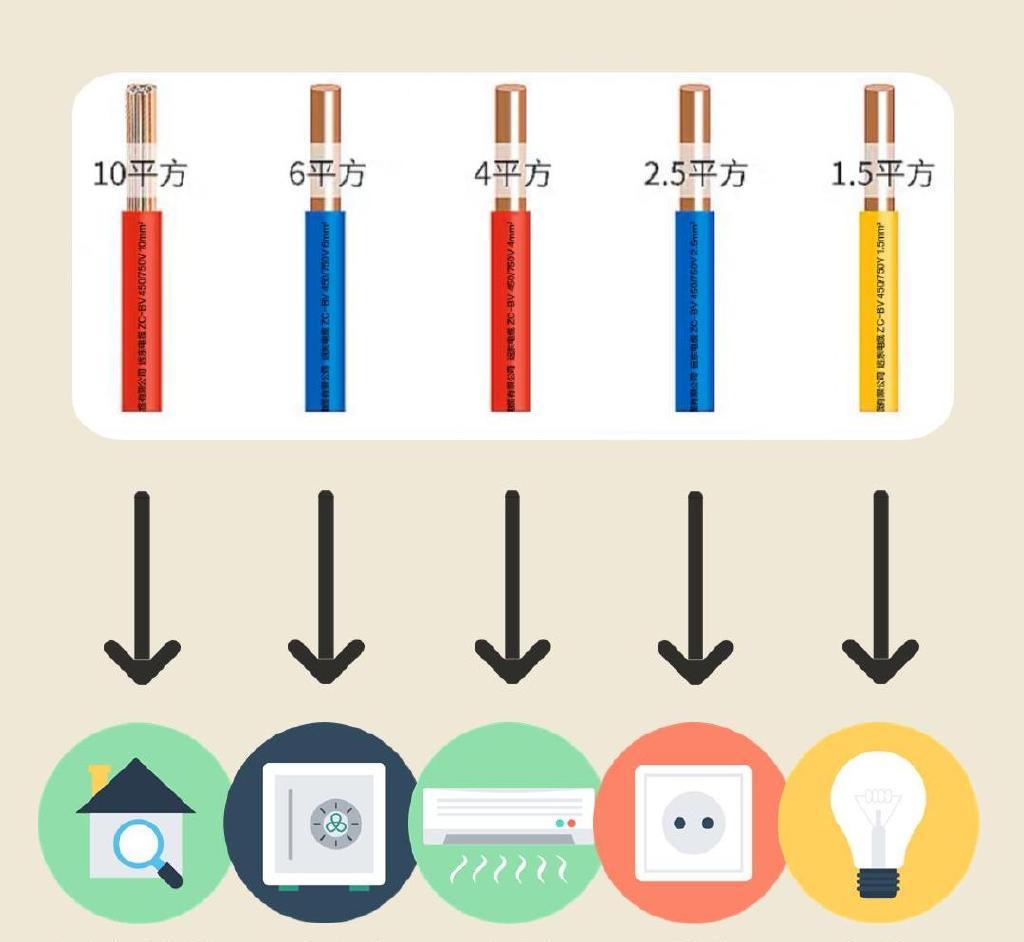

Conductor Selection: How Wire and Cable Thickness Shapes the Fate of Current Flow

Zusammenfassung:

The cross-sectional area of wire and cable conductors is far from a simple physical dimension; it profoundly influences the efficiency, cost, and safety of current transmission. This article deeply analyzes the multi-dimensional relationships between conductor thickness and resistance, current-carrying capacity, energy consumption, temperature rise, economy, and material innovation, reveals the core logic of scientific selection, and provides key guidance for optimizing power transmission.

In the surgingof electricity and information, wires and cables act as invisible lifelines. The millimeter-scale difference in the cross-sectional area of the conductor within them often determines the success or failure of current transmission—whether it is a smooth path of high efficiency and low loss, or a risky road of energy dissipation and overheating.

1. Law of Resistance: The Physical Foundation of Thickness and Energy Loss

- Argument: The resistance of a conductor is inversely proportional to its cross-sectional area, the core physical mechanism through which thickness affects current transmission.

- Evidence: According to Ohm’s Law (V=IR) and the resistance formula (R = ρL/A), conductor resistance (R) is proportional to the material’s resistivity (ρ) and length (L), and inversely proportional to the cross-sectional area (A). This means that for the same material (ρ) and length (L), the thicker the conductor (larger A), the smaller the resistance (R). The Joule heat loss (P_loss = I²R) generated by current (I) is significantly reduced. For example, doubling the conductor area theoretically halves the resistance and cuts power loss by half under the same current (the International Electrotechnical Commission IEC 60287 series standards specify cable loss calculation methods in detail).

- Impact: Thick conductors form the physical basis for efficient, low-loss power transmission, especially in long-distance and high-current scenarios.

2. Current-Carrying Capacity: The Width Scale of Safe Passageways

- Argument: Conductor thickness directly determines the upper limit of its safe current-carrying capacity (ampacity).

- Evidence: Current flowing through a conductor inevitably generates heat. The thinner the conductor, the higher the current density (J = I/A) per unit cross-sectional area, leading to more concentrated Joule heating and faster temperature rise. If the heat resistance limit of the insulating material is exceeded, it will cause insulation aging, breakdown, or even fire. Therefore, the conductor must be thick enough to ensure its operating temperature stays within a safe range based on the expected load current. National and international standards (such as NEC NFPA 70 in the U.S. and IEC 60364 internationally) specify the rated current-carrying capacity for conductors of different cross-sectional areas, materials, insulation types, and laying methods (e.g., the NEMA Wire Gauge AWG Standard Ampacity Table). Using thin conductors for high currents is a major safety hazard.

- Impact: Conductor thickness is a key defense to ensure power safety and prevent overload fires.

3. Voltage Drop: The “Toll” for Electricity to Reach Its Destination

- Argument: The voltage drop in a circuit is proportional to conductor resistance, directly affecting the power supply quality of end devices.

- Evidence: According to Ohm’s Law, current flowing through line resistance (R_line) causes a voltage drop (ΔV = I R_line). The thinner the conductor, the larger R_line and ΔV. Excessive voltage drop can result in insufficient voltage for end devices (e.g., motors, lighting), manifesting as difficult motor starting, dim lights, reduced efficiency, or even device damage. *For long-distance power supply lines or precision equipment requiring voltage stability, the conductor cross-sectional area must be increased to reduce R_line and control the voltage drop within allowable limits (typically specified as no more than 3–5% of the rated voltage, referring to codes like IEEE Std 141).

- Impact: Thick conductors are essential to maintain stable supply voltage and ensure normal, efficient device operation.

4. Economy: The Game Between Initial Investment and Long-Term Operation

- Argument: Conductor thickness selection is a trade-off between initial material costs and long-term operation energy costs.

- Evidence: Thicker conductors require more copper, aluminum, or other metallic materials, usually increasing initial procurement costs and installation difficulty/costs (e.g., weight, bending radius). However, the low resistance of thick conductors means lower operation energy costs (power loss expenses). Thus, there is an economic current density or optimal cross-sectional area: when the line load is high, annual operation time is long, and electricity prices are high, increasing the cross-sectional area—though raising initial investment—can lower long-term total costs (initial + operation costs) due to significantly reduced line losses (Life Cycle Cost Analysis, LCCA, is a key tool). A U.S. DOE report notes that optimizing conductor size is a critical measure to improve energy efficiency in industrial facilities (U.S. DOE – Improving Motor and Drive System Performance).

- Impact: Scientific selection requires moving beyond mere low-cost procurement thinking to conduct full life cycle cost accounting for optimal economy.

5. Temperature Rise and Service Life: Heat as a Hidden Killer of Insulation

- Argument: Overheating caused by thin conductors accelerates insulation aging and shortens cable life.

- Evidence: As mentioned, thin conductors under high current have high resistance losses and temperature rise. Sustained overheating accelerates thermal aging processes (e.g., oxidation, embrittlement) in cable insulation materials (such as PVC, XLPE, EPR), irreversibly degrading their mechanical and electrical insulation properties (e.g., dielectric strength). This not only increases failure risks (short circuits, ground faults) but also directly shortens the cable’s design service life. Experimental data shows that for every 8–10°C the insulation working temperature exceeds its rated temperature (Arrhenius’ law), its life may be halved (refer to IEEE Std 101 for insulation life assessment).

- Impact: Choosing sufficiently thick conductors to control operating temperature is central to ensuring long-term reliable cable operation and extending asset life.

6. Materials and Structures: Breaking Through the Physical Limits of Thickness

- Argument: Conductor material properties and structural innovations can partially “transcend” the limitation of improving performance solely by increasing cross-sectional area.

- Evidence:

- High-conductivity materials: Using materials with lower resistivity (ρ), such as oxygen-free high-conductivity copper (OFHC), can achieve lower resistance at the same cross-sectional area, equivalent to “effectively thickening” the conductor. Emerging materials like carbon nanotubes and graphene have lower ρ and higher theoretical current density potential (Nature materials science frontier research).

- Composite conductors/structures: For example, steel-reinforced aluminum cables (ACSR) are commonly used in medium-to-high voltage overhead lines, where aluminum conducts electricity (utilizing its low density) and the steel core provides mechanical strength, offering better comprehensive performance than simply increasing pure aluminum conductor area. Special structures like segmented conductors and transposed wires optimize current distribution and reduce alternating current resistance (skin effect, proximity effect).

- Superconducting technology: Achieving zero resistance at extremely low temperatures allows theoretically infinite current carrying without loss, completely breaking free from conductor thickness limitations (e.g., U.S. DOE superconducting projects explore applications).

- Impact: Material and structural innovations provide new paths for optimizing current transmission in scenarios with space/weight constraints or extreme efficiency requirements.

Conclusion:

Conductor thickness is far from a simple dimensional parameter; it is a core engineering variable profoundly influencing current transmission efficiency, safety boundaries, power quality, economy, and cable life. While thin conductors have low initial costs, their high resistance leads to significant energy consumption, voltage drop, overheating risks, and shortened life, making them costly in high-current, long-distance applications. Thick conductors, though requiring higher upfront investment, offer low loss, high safety, superior voltage quality, and long life, proving invaluable in critical applications. The ideal choice is never “the thicker, the better” or “the thinner, the cheaper,” but a precise balance based on physical laws (resistance, current carrying, temperature rise), accurate calculations (ampacity, voltage drop, line loss), and full life cycle cost analysis.

With continuous breakthroughs in high-conductivity materials, composite structures, and even superconducting technology, future conductor design will have broader optimization space. However, no matter how technology evolves, a deep understanding of the complex and delicate interaction between conductor cross-sectional area and current transmission remains the cornerstone for power engineers and users to make informed choices, ensuring safe, efficient, and economic system operation. The expert team at Zhujiang Cable deeply understands this, committed to providing you with conductor selection consulting based on precise calculations and rich practice, helping your power lifelines flow unimpeded.